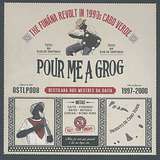

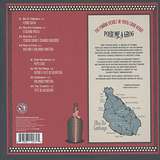

Various Artists: Pour Me A Grog: The Funana Revolt in 1990s Cabo Verde

Beautiful presented compilation of stunning cumbia close Funaná music (comes w/ valuable booklet & download code) (w/ download code)

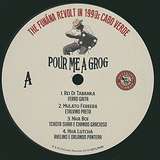

- A1 Rei Di Tabanka

- A2 Mulato Ferrera

- A3 Nha Boi

- A4 Nha Lutcha

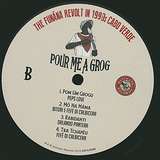

- B1 Pom Um Grogu

- B2 Mô Na Mám

- B3 Rabidanti

- B4 Tra Tchapéu

In the 1950s, a few young men, known as Badius, embarked on a nearly 2,500-mile (4000 km) journey from the northern rural interior of Cabo Verde’s Santiago Island to the island of São Tomé off the Atlantic coast of central Africa. Incredibly, they made the arduous journey not to earn a better living or send money back home — but to simply buy an accordion, locally known as a gaita. They would work years in harsh conditions to earn enough to buy the instrument and a few more years to buy a ticket back to Santiago.

Returning home, they slowly formed an elite class of self-taught gaita players who achieved a status similar to the griots of West Africa: venerated: wise elderly men archiving Badiu history in their diatonic button accordions. The gaita became the maximum expression of Badiu identity, one defined over centuries by a persistent culture of revolt and rebellion against domination and injustice. In a land lacking electricity, the acoustic instrument is king.

The gaita masters marriage to a hard-won instrument gave birth to raw Funaná music, undoubtedly a trans-Atlantic sibling of Colombian Cumbia. Hypnotic notes on aged accordions, tuned and flavored in ways found nowhere but Santiago, became infused with inviting baselines, raucous rhythms, blade-on-iron percussion and the bubbling lyricism and lament of the island’s finest ambassadors, their lyrics spoke of the trials of daily scarcity and playfully crafted whole metaphors within songs.

Their music was outlawed under colonial rule, with strict curfews monitored by the ever watchful eye of Portugal’s secret police to prevent gatherings since Funaná was dance music meant for large crowds, centered on one of the many star gaiteiros. Yet, naturally defiant, Badiu Funaná continued unfazed at the risk of arrest, detention, or worse.

Funaná remained an isolated style, largely an affair for Badiu ears only. But in 1991, Cabo Verde had its first democratic election. Elections are tricky business anywhere, let alone a state divided into several islands, each needing a tailored approach. Political parties found a novel solution, perhaps even a model, to successfully get their campaign messages out to large audiences with ears wide open: music festivals. Until today, Cabo Verde plays host to dozens of festivals a year, some sponsored by the government.

The music of the proud African interior became the soundtrack of choice at campaign rallies and music festivals. It drew large crowds, engaged the youth, kept people content, and undoubtedly won votes, setting the stage for traditional Funaná’s entry into the mainstream. But professional production and recording remained elusive.

Younger artists empowered by the politically-backed proliferation of Funaná in the early ‘90s began traveling inland to learn the trade secrets from the gaita griots, taking up the once maligned artform to counter what they saw as global pop sounds diluting Cabo Verdean output and preventing genuine local music from competing on the airwaves.

Another revolt was afoot, and in 1997, an “earthquake shook the country,” a Cabo Verdean newspaper wrote, when a group of youths, calling themselves Ferro Gaita, “dared to make a disc based on the gaita, ferrinho and bass guitar.” That best-selling first album -- 40,000 copies in a country of just 400,000 -- changed the entire trajectory of the country’s music.